오늘 Inside Art 메일에 Gustav Klimt 에 관한 그림 이야기가 있어 옮긴다.

(번역은 또 구글 번역 그대로, 영어 원문은 맨 마지막에 )

오스트리아 상징주의 화가 구스타프 클림트(1862-1918)는 석유, 금박 및 기타 귀금속을

사용하여 꿈 같은 여인을 그린 실물 크기의 3/4로 그림으로 잘 알려져 있습니다.

예를 들어, 금박, 은, 백금이 추가된 1907~08년의 캔버스에 유화로 그린 키스(The Kiss)는

사랑의 상징으로 남아 있으며 포스터, 머그잔, 우산, 달력, 스카프, 기타 등등에

수천 번 복제되었습니다. (상품 판매는 우리 문화가 보편적인 감탄을 위해 특정 그림을

선택했음을 알리는 방식인 것 같습니다.)

또는 같은 시기의 Klimt의 Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I(The Lady in Gold 또는

The Woman in Gold라고도 함)을 고려해보세요(아래).

또한 당시의 초현대적 아르누보와 예술 공예 운동의 영향을 받은 이 작품은 마지막

작품이자 클림트의 "황금기" 그림을 가장 대표하는 작품으로 간주됩니다.

비엔나 세기가 바뀌면서 클림트는 아름다운 여성의 화가였습니다.

비평가들은 클림트가 "[클림트의] 세계관에서 본질적인 에로틱한 요소의 기초"로서

주제를 상쇄하기 위해 그리고 신성하거나 마술적/동화적인 특성을 불러일으키기 위해

금을 사용했다고 보고 있습니다.

그러나 풍경은 클림트 생애 마지막 20년 동안 작품의 거의 절반을 차지합니다.

클림트는 자신만의 회화적 언어를 가지고 있었고, 그의 풍경화는 그것을 유창하게

표현하고 있습니다. 덜 알려져 있지만 매우 중요한 것은 클림트 학자인

스테판 코자(Stephan Koja)는 "그들은 우리를 그의 예술의 핵심으로 이끈다"고 말합니다.

“우리의 눈은 주제와 내용에 의해 방해받지 않고 순수하게 예술적인 본질을 향하고

있습니다. 이 작품을 통해 클림트는 자신의 진정한 위대함을 달성했다는 것이 분명해졌습니다.”

그 풍경화들은 말 그대로 놀랍고 강렬하고 정밀하게 칠해져 있으며 여름의 빛과

생명으로 반짝입니다.클림트는 비극의 탄생(1886)에 출판된 프리드리히 니체의

예술 이론을 알고 있었는데, 여기서 예술과 아름다움은 삶의 잠재적인 무의미함에

대한 균형 잡힌 보상으로 제시되었습니다.

아름다움은 고통을 변화시킨다고 철학자는 썼습니다. 클림트는 그의 그림이

"환상을 통한 구원"을 제공하고 관객에게 "환상의 아름다움에 완전히 휩싸인" 느낌을

주기를 원했습니다. (구스타프 클림트의 스테판 코자, 풍경, 프레스텔, 2006)

클림트는 초상화에 가져온 것과 동일한 접근 방식을 풍경에도 적용했습니다.

클림트는 동일한 언어를 사용하지만 두 장르에서 서로 다른 말을 하기 때문에

다르게 보입니다. 그럼에도 불구하고 미학은 동일합니다.

클림트는 자신의 즐거움과 돈을 벌기 위해 풍경을 그렸습니다.

이를 통해 그는 순전히 예술적인 질문을 다루고 자신의 경제적인 수익보다

더 공식적인 경계를 테스트하고 깨뜨릴 수 있었습니다.

그 안에서 우리는 클림트 예술의 본질을 발견합니다. 그의 대담한 문체 전개,

"그의 색채적 광채, 정밀하게 세부적인 그림 구성, 대상과의 거리두기에 의해

제어되는 편재하는 관능성, 표면의 견고한 구성"을 보여줍니다. (같은 책, 풍경).

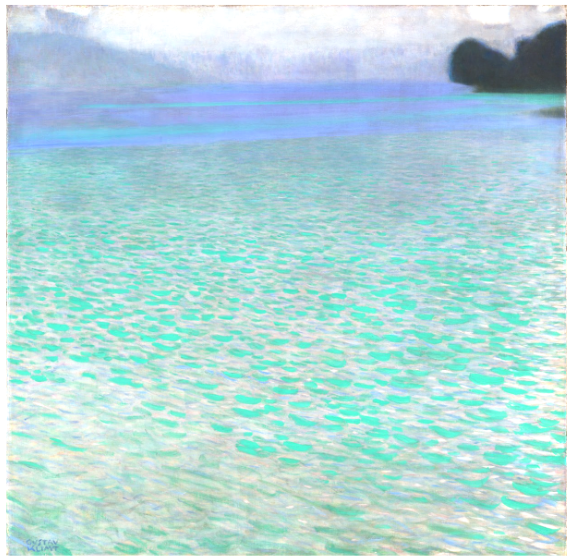

클림트의 여름 오스트리아 아터제 호수에서 그려진 이 그림(위)은 모네의

물 처리와 DNA를 공유합니다. 그러나 클림트는 (정사각형!) 캔버스의 90%를 반짝이는

깨진 색상으로 만들어 보다 대담하고 추상적인 구성을 만들었습니다.

이 작품은 최근 뉴욕 소더비 경매에서 일본 개인 구매자에게 5,320만 달러에 팔렸습니다.

1940년에 처음 전시된 이 작품은 표면적으로 클림트의 작품을 북미 시청자들에게 소개했습니다.

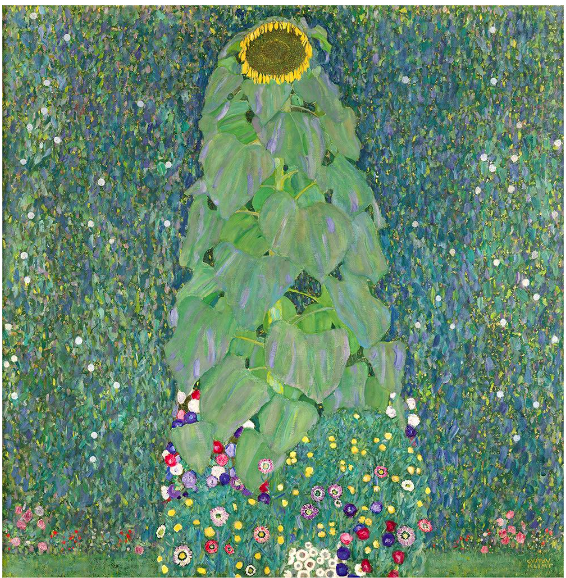

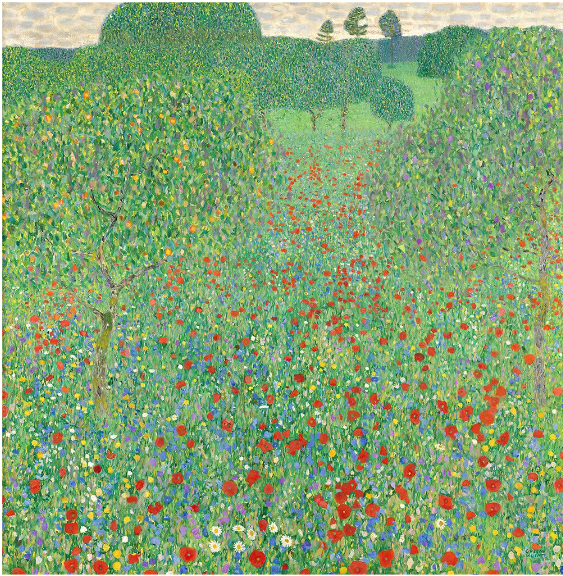

아래의 그림은 클림트가 아테제에서 휴가를 보내는 동안 그린 많은 풍경 중 하나입니다.

다음은 같은 시간과 장소에서 나온 클림트의 조경 작품 중 몇 가지 뛰어난 예입니다.

내 눈에는 클림트가 그린 지 100년이 지난 지금도 그 그림들이 믿을 수 없을 정도로 생생하게 남아 있습니다.

구스타프 클림트, 아터제 호수, c. 40 x 40인치, 1901-1908

Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) is well known for his 3/4 life-size fin de siècle paintings of dreamlike women in oil, gold leaf, and other precious metals. The oil-on-canvas painting The Kiss of 1907-08, for example, with added gold leaf, silver, and platinum, remains a beloved emblem of love, reproduced thousands of times on posters, mugs, umbrellas, calendars, scarves, you name it. (Selling merch seems to be how our culture signals that it’s chosen a particular painting for universal admiration.)

Or consider Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (also called The Lady in Gold or The Woman in Gold) of the same period (below). Also influenced by then ultra-modern Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements, it’s the final and considered the most representative of Klimt’s “Golden period” paintings. In turn of the century Vienna, Klimt was THE painter of beautiful women. Critics look back on Klimt’s use of gold to offset his subjects as “underlying the essential erotic ingredient in [Klimt’s] view of the world” coupled with the medium’s ability to conjure a sacred or magical/fairy-tale quality.

But landscapes make up nearly half of Klimt’s output during the last two decades of his life. Klimt had his own pictorial language, and his landscapes speak it fluently. Lesser known but of major importance, “they lead us to the verry core of his art,” says Klimt scholar Stephan Koja. “Our eyes are directed at the essentials, the purely artistic, unobstructed by theme and content. It becomes apparent that, in these works, Klimt achieved his real greatness.”

They are almost literally stunning, so intensely and precisely painted are they, and so sparkling with summer light and life.

Klimt knew Friedrich Nietzsche’s theories of art as published in The Birth of Tragedy (1886), where art and beauty are held up as the balancing compensation for life’s potential meaninglessness. Beauty transforms suffering, the philosopher wrote, and in much the same way, Klimt wanted his paintings to provide “salvation through illusion” and to offer the viewer the feeling of “being absolutely engulfed in the beauty of illusion.” (Stephan Koja in Gustav Klimt, Landscapes, Prestel, 2006)

Klimt applied the same approach to his landscapes that he brought to his portraits. They look different because while Klimt is using the same language, he’s saying different things in either genre. Nonetheless, the aesthetic is the same.

Klimt painted his landscapes for his own pleasure and to make money. They allowed him to deal with purely artistic questions and to test and break more formal boundaries than in his commissions. In them, we find the essence of Klimt’s art: they demonstrate his bold stylistic development, “his coloristic brilliance, precisely detailed pictorial composition, omnipresent sensuality, controlled by the distancing from the object, and the rigid organization of surface.” (Ibid., Landscapes).

Created during Klimt’s summer on Attersee Lake in Austria, this painting (above) shares DNA with Monet’s treatment of water. However, Klimt created the more daringly abstract composition, yielding 90 percent of the (square!) canvas to shimmering broken color. This work recently changed hands in an auction at Sotheby’s in New York City, where it sold for $53.2 million to a private buyer in Japan. First exhibited in 1940, this work ostensibly introduced Klimt’s work to a North American viewership.

It’s among the many landscapes Klimt painted while vacationing at Attersee, including its sister painting below. Following which are several more outstanding examples of Klimt’s landscape work from the same time and place. To my eye, they’re still incredibly fresh and alive more than 100 years after Klimt painted them.

'기타 등등( Misc.)' 카테고리의 다른 글

| ( 기타 ) 17 Gorgeous Sky Paintings (0) | 2024.11.17 |

|---|---|

| ( 기타등등 ) 사진처럼 정교한 수채화 그림 ( V) (5) | 2024.09.10 |

| ( 기타) PleinAir Salon Art Competition ( from PleinAir Magazine) (2) | 2024.03.07 |

| ( 기타 등등 ) 예술작품에서 나타난 아름다운 연인들의 모습 (5) | 2024.02.15 |

| ( 기타 ) 사진처럼 정교한 수채화 그림 ( VI ) (2) | 2024.02.01 |